There’s nothing says that you’re in England more-so than a place name like ‘Crackpot’ (in Swaledale, North Yorkshire to be precise). One of the many joys of being a Landscape Architect is the need for us to explore, and when we do, we’re surprised by place names more often than you’d think.

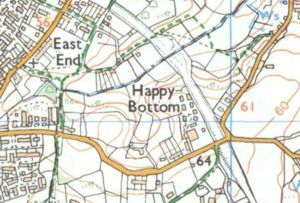

My recent Visual Impact Assessment of a proposed housing development in Wimborne Minster includes viewpoint 44, located at ‘Happy Bottom’. In the course of undertaking similar fieldwork, I’ve also visited ‘Scotland’ (near Liss, in Hampshire), and ‘Quebec’ (near Harting, in West Sussex). Out on the road I’ve been amused driving through ‘Worlds End’ (near Denmead, in Hampshire), and invariably on route to visit my Mum in Shropshire there comes a point when I’m at ‘Loggerheads’. When I first started out as a Landscape Architect, I did a design for a school in Wootton Wawen (in Warwickshire). Try saying that after a couple of pints. I would mention a favourite old Terra Firma scheme at ‘Sandy Balls’ (in the New Forest) – but we would not wish to cause offence to client, inhabitants or indeed the many who visit there.

Place names are a constant fascination to me. Not only do they often make me smile as I go about my work, but they nearly all (even the less amusing ones) make me reflect on the origins of the place. How do places become known by then names we associate with them? It would seem that it is rarely deliberate but often a quirk relating to some long-forgotten human intervention centuries back.

Human intervention is the very essence of the work of a Landscape Architect. A site we’ve designed including a prominent tree may have slipped our mind in 20 years’ time. But in that space of time, the tree may have become important in the minds of local people. They may associate it with the landowner. In another 20 years’ time, the landowner may sell the land and housing may be built on it. The tree may be kept, and the way people refer to it may stick. They may still call it ‘Mr. So-and-so’s tree’ – even though Mr. So-and-so is no longer around. The name might become synonymous with the place, not just the tree. After all, it’s believed that the Saxon origin of the name ‘Coventry’ is derived from ‘Mr. Cofa’s Tree’.

Once upon a time, somebody made the decision to plant some Oak trees – 7 of them. Eventually, that place became known as Sevenoaks. Or on a more local scale, sometimes you’ll come across street names referring to a tree. Even though ‘Elm Grove’ may no longer have any Elm trees, at some time in history somebody would have decided to plant the trees that gave the place its name.

Place names are littered with examples of how our predecessors have designed Landscapes in the past. Without knowing it, we might also create history in a similar way – a way that is almost indelible. Something which makes a ‘place’ different to a ‘plot’ is when a community collectively gains a perceptive association with it – and for ease of conversation the location often becomes intrinsically referred to by name. This possibility that an echo of our day-to-day designs could resonate long into the future (long outliving the original creations themselves) is all the more intriguing because it’s a quirk of fate, out of our hands. It’s a joy to think that our designs can take on a life of their own.